Monarch Update

By Paul James

At a press conference in Mexico City last January, scientists cheered when the official eastern monarch butterfly population was announced. And with good reason: The numbers were an impressive 144% increase over the previous year, and the highest recorded since 2006. At the same time, however, it was announced that the California western monarch population had declined by a stunning 86%. So what gives?

Most scientists agree that the increase is likely due to favorable weather conditions during the spring and summer breeding seasons and the fall migration. But they warn that one good year, while worthy of celebration, doesn’t mean the population will continue to rise.

“This reprieve from bad news on monarchs is a thank-you from the butterflies to all the people who planted native milkweeds,” said Tierra Curry, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity. “But one good weather year won’t save the monarch in the long run, and more protections are needed for this migratory wonder and its summer and winter habitats.”

The population figure of the eastern monarch – the one that travels through Oklahoma – is based on how many acres of trees the overwintering butterflies inhabit in the mountain forests of Mexico. In 2018 that number was 14.9 acres; in 2013 it was a mere 1.7 acres. The target for monarch recovery is a sustained 15 acres, but if the past 20 years is any indicator, that may be an elusive goal at best.

But still, there’s hope. Here in Oklahoma, interest in creating and expanding monarch habitat is at an all-time high. Sales of milkweed have skyrocketed, and more gardeners than ever are focusing on plants that attract adult monarchs as well, who need nectar and pollen to survive. (To learn more about how to help ensure thriving monarch migrations for generations to come, consider joining the Oklahoma Monarch and Pollinator Collaborative. For details, go to www.okiesformonarchs.org.)

And every other state in the monarchs’ migratory pathway is doing likewise. So to the extent that these efforts can offset the damage done by pesticides and habitat loss, I’m hopeful that the recovery seen in 2018 is indeed sustainable. After all, I can’t imagine a world without monarch butterflies, and I’m pretty sure you share my sentiment.

Note: Incidentally, the dramatic decline in California’s monarch population – down from 1.2 million two decades ago to a mere 30,000 now — is being attributed in large part to wildfires and the resulting loss of habitat, but pesticide use remains a problem as well. The current numbers mean that the western monarch butterfly, which overwinters in coastal California rather than central Mexico, is on the verge of extinction.

Leaves of Three, Let it Be!

By Paul James

I was hiking with my five-year-old grandson not too long ago, and we came upon a large batch of poison ivy. “Leaves of three, let it be,” I said, to which he replied, “Huh?” I’m pretty sure I had the same puzzled look on my face when my grandfather said the same thing to me 60 years ago. But you’re never too young to learn how to recognize poison ivy, and you’re never too old to learn how to get rid of it.

Oddly enough, poison ivy is related to cashews (I know, that sounds nuts) as well as pistachios, mangos, sumac, and the ornamental smoke tree. It’s a native plant as well, one that grows in every state except California (where they have the dreaded poison oak instead). And although we tend to despise it, poison ivy is important ecologically as a source of food for wildlife. Birds love the fruit it produces, as do deer and mice. And many insects eat the foliage.

About 10 to 15 percent of the human population is immune to poison ivy, or more specifically urushiol, the chemical responsible for giving the rest of us a nasty rash. I know a guy who can sleep in a bed of poison ivy and wake up unfazed. But I’m not that lucky, and chances are neither are you. So when I see poison ivy, all I want to do is get rid of it.

One way to do that is to dig it up, roots and all, but not before donning long pants, a long-sleeved shirt, and gloves, all of which must be washed or tossed immediately after. It’s also a good idea to apply a product called Tecnu (available at drug stores and online) to exposed skin both before and after exposure. And fair warning – if you leave behind one tiny piece of rhizome in the ground, you’ll soon have more poison ivy, which is why you’ll want to dig at least eight-inches deep to get all the roots. When you’re done, bag up the vines and trash them, and wash your tools too.

You can also smother the plants by covering them with cardboard, carpet remnants, or black plastic. It’ll likely take several months to kill the plants outright, but it does tend to minimize your risk of exposure.

Of course, the easiest approach is to rely on an herbicide, preferably one that’s labeled for vines or poison ivy specifically. Most of them contain either glyphosate or triclopyr, both of which are synthetic chemicals. However, there’s an organic alternative called Pulverize Weed, Brush, and Vine Killer that works great as well, although two applications may be necessary to eradicate the vines.

A few things to keep in mind when working around poison ivy: every part of the plant is poisonous; the urushiol is present in the stems even when the plant is dormant; and you can still get a rash long after the plant is dead. Whatever you do, don’t burn the plants because the urushiol can get into your eyes and lungs.

Finally, realize that poison ivy leaves can be dull or shiny, the leaf margins may be smooth or serrated, and the little stems (petioles) that connect the leaves to the main vine may not always be red. In other words, there’s no one poison ivy. In fact, not all species have three leaves. There’s one in Texas that has five leaves, which is no surprise of course, since everything’s bigger in Texas.

Joe Gardener & Me

By Paul James

Late last month, I flew to Atlanta to tape a television show with Joe Lamp’l, host of Growing a Greener World on PBS. In addition to the show, Joe has a huge presence on the web, and his website, joegardener.com, is a treasure trove of excellent information. He also offers online gardening courses, cranks out a regular podcast, and is all over social media. So why did he invite me to be on his show?

Well according to Joe, one of the most frequent questions people ask him when he’s on the road is, “Where in the world is Paul James?” So to let people know that I’m not yet pushing up tulips, I agreed to appear on his program, which was shot over a two-day period at his five-acre property north of Atlanta.

Up to that point, I’d never spent much time with Joe, but I’ve admired his work for years. And I quickly discovered that he’s not only a very kind, generous, and gracious guy – he’s also the real deal. By that I mean he’s a gardener’s gardener (and an organic-gardening purist as well) with an impressive depth of knowledge. For that reason, it made me more than a little proud to hear him say that I had actually inspired him over the years.

I hadn’t taped a 30-minute program since I stopped doing Gardening by the Yard back in 2008, but it didn’t take me long to get up to speed. For one thing, Joe’s small but extremely talented and dedicated crew put me at ease in no time, and his gorgeous garden offered instant inspiration.

We talked at length about all sorts of topics – from gardening to my history with HGTV to my current endeavors – and I have to say I had a blast. That was the first time I’d ever been a guest on someone else’s show, which meant I didn’t have to wear all the hats I once did (writer, producer, director, host). All I had to do was talk, and for me that’s pretty darn easy.

Joe tells me the show will likely air sometime in September or October. I’ll keep you posted. In the meantime, check out what all Joe is up to by clicking these links.

GrowingAGreenerWorld.com

joegardener.com

The joe gardener Show Podcast

Facebook.com/joegardener

facebook.com/GGWTV

twitter.com/joegardener

twitter.com/GGWTV

instagram.com/joegardener

Watering Myths

By Paul James

After a week in the mountains around Santa Fe, with lows in the 50s and highs in the 70s, I was less than excited to return home to sweltering heat and humidity. But then it is the middle of July, after all, so I had no reason to be surprised. After unpacking, I headed out to the garden to water, and that got me to thinking about a number of myths I frequently hear about watering. Seven myths to be exact.

MYTH #1: PLANTS REQUIRE ONE INCH OF WATER A WEEK

I’ve never been a fan of this popular recommendation for two reasons. First, how in the world do you know when you’ve delivered an inch of water to plants? And second, it’s just plain bad advice.

Fact is, the moisture needs of plants vary enormously. For example, newly seeded beds, young seedlings, and new transplants need water every day, maybe even twice a day in summer. The same is true of patio pots and hanging baskets (and in my case at least, bonsai).

Newly planted trees and shrubs are sure to die if they receive only an inch of water a week. It’s best to water them with a slow trickle from the hose, moving the hose around the perimeter of the root ball now and then, ideally for about as long as it takes you to casually consume one beer. Or even two. Depending on your soil type, you may need to repeat the process every three or four days.

Mature trees and shrubs, on the other hand, may not need much (if any) supplemental watering even during the summer months. I occasionally water my tree-filled lawn, but in 40 years I’ve never actually watered a mature tree.

And Bermuda grass can get by with as little as an inch of water every four to six weeks. Fescue, however, should be watered every week.

Now in defense of the myth, I suppose that if everything in your landscape is fully established, meaning every plant has been in the ground for at least three years, odds are most everything growing will survive with only an inch of water a week. But I can assure you few things will actually thrive.

MYTH #2: WHEN PLANTS WILT THEY NEED WATER

That certainly can be the case, but wilting may be due to something other than a lack of water. Wilting can also be a sign of overwatering, because water-logged soils can suffocate plants. And even plants that have plenty of moisture available to them can wilt on really hot days, because they tend to lose moisture through their leaves faster than their roots can take it up.

MYTH #3: WATERING ON A SUNNY DAY CAN SCORCH LEAVES

This commonly held notion is ridiculous. Water droplets don’t act as a magnifying glass on plant leaves.

MYTH #4: AUTOMATIC SPRINKLER SYSTEMS ARE THE BEST WAY TO WATER

I would argue the opposite, actually. Not because there are inherent flaws in sprinkler systems, but because at least 75% of the time the systems are set improperly.

The vast majority of sprinkler timers are set by the installer, whose expertise is in irrigation systems, not plants. So the installer sets the timers to run for 10 or 15 minutes in the morning and very often another 10 or 15 minutes in the evening as well. In most cases, and especially if your gardens are well mulched, that’s nowhere near enough time to deliver a sufficient amount of water to the root zones of plants. Instead, it results in water barely percolating into the soil, which means roots hover in that moist, shallow zone rather than reaching farther down into the soil.

I had an irrigation system for 15 years at a previous home, and I never set it to run automatically unless I was on vacation. Instead, I would turn it on manually to water select zones at different times during the week, and I would adjust the run time of each zone depending on what was growing. I suggest you do likewise.

Now I water by hand, which is in my opinion the only way to know with certainty just how much water every plant gets. And as a bonus, it puts me more in touch – and in tune – with my garden.

MYTH #5: OVERHEAD SPRINKLERS ARE BAD

While it’s true that it’s best to water the base of plants rather than the foliage to minimize fungal diseases, there are times when it’s perfectly okay to water plants overhead. As a matter of fact, after prolonged periods of dry, windy days, I prefer to water overhead to knock off all the accumulated dust on leaf surfaces. What’s more, overhead watering helps cool down heat-stressed plants.

MYTH #6: WATER ONLY IN THE MORNING

Sure, it’s best to water in the morning, but not everyone’s schedule allows for what’s best. Basically, you should water whenever you can. And deep soak each time you water.

MYTH #7: DROUGHT-TOLERANT PLANTS DON’T NEED TO BE WATERED

Even cacti and succulents, which are among the most drought-tolerant plants, need water, especially during their first season. Beyond that, they’ll need water less frequently, but they’ll still need to be watered now and then. In my experience, even drought-tolerant plants grow better with a regular supply of moisture.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Ultimately, the only way to know if your plants are getting enough water is to stab a shovel or trowel into the soil, pull it back to reveal the soil profile, and see for yourself just how deep the water is percolating into the soil. It’s not exactly a high tech method, but it is the best method.

Vegetable Origins

By Paul James

When you sit down to eat, do you ever wonder where the carrots or broccoli or tomatoes on your plate actually came from? Well of course they came from a farm, but that’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about where they came from originally and the paths they took to ultimately wind up here. And along the way, who in the world figured out what was edible and what wasn’t?

Ancient hunter-gatherers were the first to experiment with eating plants – leaves, stalks, roots, whatever. It’s certain that not every taste test was successful, and that some were downright fatal. But thankfully, plants that are poisonous typically contain alkaloids that are quite bitter, and that’s one of the ways the hunter-gatherers learned to select what to eat and what not to eat. But still, you gotta wonder how many people croaked when they saw deadly nightshade or water hemlock and thought it might go well with roasted saber-tooth tiger or grilled mastodon.

As for food origins, it turns out we know a great deal about where vegetables came from thanks to ancient texts and archaeological digs. But there’s still a good deal we don’t know.

Take peas, for example. Modern botanists are convinced that peas have their roots in a region extending from the Mediterranean eastward to central Asia. But the only archeological evidence we have of peas is from a cave in Thailand dating back to 9750 B.C. Radishes probably originated just east of the Mediterranean in western Asia, but since so many wild varieties exist even today, it’s hard to pinpoint exactly where they came from originally.

So I’ve chosen to focus on a few vegetables about which we know quite a bit in terms of where they came from and how they got to this country.

Onion – Allium cepa

Onions are arguably the oldest of the vegetables we eat. The earliest known reference is a Sumerian cuneiform tablet from around 2400 B.C., but they were likely cultivated a century or more before in central Asia.

Onions are immortalized in an inscription at the Great Pyramid at Giza, where laborers were fed onions, radishes, and garlic with every meal. They were also used in the mummification process.

Greeks and Romans also enjoyed onions. In Nero’s Rome, gladiators were massaged with onion juice before entering the arena to keep their bodies firm. And like tomatoes (more on them in a moment), onions were considered powerful aphrodisiacs. A basket of onions was recovered from the ruins of Pompeii in, of all places, the town’s biggest brothel.

By Elizabethan times, onions were being eaten pretty much the world over. They spread rapidly because they kept well in storage.

The domesticated, globe-shaped yellow onions, first cultivated extensively in Spain, came to America on the Mayflower, although wild onions had been growing here long before the settlers arrived. They were an instant hit, however, and were eaten in every way imaginable – roasted, boiled, pickled…even raw. George Washington grew onions, and described them as “the most favored food that grows.”

Carrot – Daucus carota

The first carrot wasn’t orange. It was purple. And it was hardly the plump, uniform shape we enjoy today. In fact, carrots were gnarly, misshapen, and scrawny. However, they were edible, and in ancient Afghanistan, home of the original carrot, they provided sustenance.

By the time carrots reached ancient Greece and Rome, and thanks to natural selection, they were larger and fleshier, but they were still highly branched.

The familiar conical root we know today showed up in the 10th or 11th century in Asia Minor, and arrived in Spain in the 12th century by way of the marauding Moors. By that time, thanks to a pigment known as anthocyanin, there were purple, violet, red, and even black carrots. A pale yellow carrot arrived on the scene 400 years later. But even in the 16th century, there were no orange carrots.

Finally, in the 17th century, a Dutch carrot breeder came across an orange carrot, and the orange carrots we eat today are direct descendants of that 400-year-old discovery.

The carrot arrived in North America with the first settlers of Jamestown. It was popular from day one, although so many people planted them in subsequent years that the domesticated carrot escaped into the wild and reverted to its original form – the weed known as Queen Anne’s lace.

Cabbage (Broccoli and Cauliflower)

Cabbage has been around for thousands of years. The Greeks ate lots of it, and the Romans absolutely loved it. To them, it was a vegetable of status. Its original wild ancestor was a seaside dweller, native to the Mediterranean, which over thousands of years would spawn kale, collards, heading cabbage, kohlrabi, broccoli, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts.

Heading cabbage didn’t arrive on the scene until around the time Julius Caesar invaded Britain. The Brits took a liking to it, and by the 16th century they were growing at least 16 different varieties, both red and green.

Cabbage arrived in the colonies by way of Canada, actually, and the response was enthusiastic. Thomas Jefferson wrote glowingly of his cabbages, especially the Savoy types.

Both broccoli and cauliflower are edible modifications of the cabbage flower, although botanists can’t agree on which came first. We know broccoli was also around in ancient Rome, but it’s hard to say precisely when. Regardless, it wasn’t as popular as cabbage.

Cauliflower, on the other hand, gained wider acceptance from the start, although it’s hard to say when that was either. There are references to it being eaten in 12th century Syria, however. Cauliflower is considered to be the most intellectual of the cabbage relatives, although Mark Twain dismissed it as “nothing more than cabbage with a college education.”

Spinach – Spinacia oleracea

Spinach hails from Asia, closer to Persia than to China. The Persians sent seeds to the emperor of Nepal as a gift in 647 A.D., where it was known as “Persian herb.” In no time at all it was growing all over China. The Chinese loved spinach and planted it along the edges of their rice paddies. But it was another four hundred years before it would arrive in Europe by way of the Moor’s conquest of Spain.

Spinach reached northern Europe in the 16th century, and quickly spread throughout the rest of Europe. Much like children today, people either loved it or hated it. Thankfully, among those who loved it was Catherine de Medici, so much so that the French phrase, a la Florentine, means spinach, in honor of Catherine’s home town of Florence.

Spinach arrived in North America in the early 17th century, but it didn’t catch on all that quickly with colonial gardeners. Then in 1784, David Landreth of the Landreth seed company of Philadelphia – whose customers included George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Monroe – developed a slow-bolting spinach called Bloomsdale, which is to this day the go-to spinach of American gardeners.

Tomatoes – Solanum lycopersicum

Given their enormous popularity – not just here in the states but around the world – it’s hard to believe that at one time tomatoes were considered unfit to eat.

The tomato is native to western South America – Chile, Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador, as well as much of Central America, including Mexico. They still grow in the wild as weedy, aggressive, ground-hugging vines. Invading Spaniards first saw them growing in Montezuma’s gardens in 1519. Cortez arrived back in Spain with seeds, and plants were soon growing all over that country. And interestingly, thanks to generations of natural selection and selective breeding, the fruits were similar to many of today’s heirloom varieties – not round, but ribbed or lobed. They called tomatoes Mala Peruviana, the apple of Peru.

From Spain, the conquering Moors took tomatoes to Morocco, and Italian sailors hauled theirs home to Italy, where tomatoes were well received in some circles but regarded with suspicion by most. They were called pomo doro, or golden apple, which suggests that the most popular tomatoes were yellow. Arriving in France a few years later, they were called pomme d’amour or love apple, largely because they were regarded as sensationally effective aphrodisiacs, and for that reason their popularity began to rise throughout Europe. But tomatoes still got a lot of bad press in Europe, primarily because they were considered poisonous, and in fact the vines are. A clever Italian herbalist in 1544 linked them botanically to deadly nightshade, which is a relative of the tomato. He called them wolf peaches, the Latinized version of which is Lycopersicon, which is essentially the current species name of the tomato.

Ultimately, however, the Italians embraced the tomato, and by the late 1500s chefs and home cooks were perfecting red sauces across the country. The French soon followed the Italian lead, and within 50 years or so no less than Henry VIII was growing tomatoes in his royal garden.

When tomatoes finally arrived in America in the mid-1600s, they were quickly condemned by ministers and physicians. The pilgrims considered them an abomination akin to dancing and card-playing. Thankfully, however, reason triumphed on behalf of the tomato thanks to Thomas Jefferson, who grew tomatoes at his Monticello farm. His own records show that he was especially fond of yellow tomatoes, which he used to make a tasty preserve.

But it wasn’t until 1820 that tomatoes gained broad acceptance in this country. Now think about that for a moment. What is today the most popular vegetable in America has only been consumed on a regular basis for 200 years.

And notice that I’ve referred to the tomato as a vegetable. Well, botanically there’s really no such thing as a vegetable. Technically, the tomato is a fruit, but if you want to get really technical, it’s actually a berry.

Regardless, the tomato is the only vegetable with a legal definition. In the United States, back in 1883, there was a 10-percent tariff on imported vegetables. A guy named John Nix refused to pay the tariff on a boatload of tomatoes from the Caribbean, insisting that they were, botanically speaking, fruits. Ten years later the Supreme Court ruled that while Nix was correct botanically speaking, in the common language of the people the tomato was nevertheless a vegetable, and Nix was ordered to pay the tariff.

Today, there are over 500 tomato cultivars on the market, but sadly, none of them are named Nix.

One more thing: modern linguists insist that the correct pronunciation is indeed to-mah-to, from the Spanish tomate. But we of course say to-may-to, and any way you slice it, at this point it’s too darn late to call the whole thing off.

Potatoes – Solanum tuberosum

Native to the Andes of South America, and capable of growing at an elevation of 15,000 feet, the first potatoes were cultivated by Peruvians – Incans, to be exact – over 6,000 years ago. These were small potatoes, ranging in size from a peanut to a plum.

The Spanish explorer Pizzaro came across the potato while pillaging for gold and other treasure in Ecuador back in the 16th century. He took a boatload of the tasty tubers back to Spain, where the harvest was used not for human consumption but rather as cattle fodder. What a shame, huh?

From Spain, potatoes made their way to Italy and France, where they were rejected on the grounds that the knobby tubers resembled the hands and feet of lepers.

The English were introduced to potatoes by way of Sir Francis Drake, who scored a shipment of them in Cartagena, Colombia. Drake gave the potatoes to his buddy Sir Walter Raleigh, who planted them at his estate near Cork, Ireland. Raleigh then gave several potato plants to Queen Elizabeth I, who gave them to her cooks to prepare. Unfortunately, the cooks prepared the poisonous vines of the plant, not the tubers, which gave the queen’s dinner guests a royal stomachache. It would be another two centuries before potatoes caught on in England.

Here in the states – just colonies at the time, actually – potatoes were anything but an instant hit when they arrived in 1622. There are a few obscure references that suggest they were planted in New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island a hundred years later, but not in any significant quantities. Basically, the potato was thought of as something you ate when there was nothing else to eat. John Adams described them in a letter to Abigail as “the worst of all vegetables.”

Meanwhile, back in France, there was a turn of events.

In the late 1750s, a French military pharmacist named Antoine Parmentier was captured in Germany during the Seven Years’ War, and while in captivity he subsisted on a diet made up of mostly potatoes. When he finally gained his freedom, he returned to France to sing the praises of potatoes for the next 30 years.

In 1785, he finally achieved his greatest success. On August 23rd of that year, in celebration of King Louis XVI’s 31st birthday, Parmentier presented the King with a bouquet of potato flowers. The King stuck one in his lapel, Marie Antoinette stuck one in her hair, and from that day forward, the potato was formally accepted as a vegetable worthy of kings, queens, and commoners alike.

Meanwhile, back in this country, potatoes were beginning to take off, again thanks to the efforts of Thomas Jefferson, among others. But it was the Irish who were responsible for its meteoric rise in popularity. The Irish Potato Famine of 1846 was responsible for the death of 1.5 million people. It also led to 1.5 million Irish men, women, and children immigrating to the United States. And those immigrants brought with them their love of potatoes. In fact, the Irish also brought with them the word spud, which comes from the Gaelic word spade.

So the next time you sit down to eat carrots or broccoli or tomatoes or whatever – I hope you’ll appreciate the circuitous and fascinating journey those and other vegetables have taken to arrive on your plate.

Shrooms in Bloom!

By Paul James

Mushrooms have been popping up in lawns all over town, and their presence causes many a homeowner to panic and wonder how best to destroy them – some sort of fungicidal spray or powder, or perhaps a pitching wedge? Well you might be surprised to learn that my approach to dealing with mushrooms in the lawn is much simpler.

That’s because I do absolutely nothing.

Truth is, I enjoy seeing the fruiting bodies of various fungi aboveground because it tells me that belowground their hyphae and mycelia (fungal roots, if you will) are busy feeding on and helping decompose little chunks of wood, old roots, and other organic matter and turning it into soil. And in the process, they’re releasing nutrients that feed the soil and plants. In other words, they’re part of a healthy soil ecosystem. Besides, fungicides absolutely will not control them, and a pitching wedge will likely do more harm to your grass than a million mushrooms ever could.

The presence of mushrooms in the lawn can tell you something about the condition of your soil, because most mushrooms prefer to grow in soils that don’t drain well. But even in soils that do drain well, excessive rainfall or overwatering can trigger their arrival.

There are a few destructive varieties of mushrooms, notably those that attack oak trees. The culprit is actually related to the shitake mushroom, but sadly once they show up at the base of a tree, there’s nothing that can be done to save it. Fairy ring mushrooms can cause damage to lawns, but if you’ll aerate and fertilize the affected area your turf should bounce back.

And of course there are poisonous mushrooms, though they’re rarely found in the lawn. Still, if you have young children or pets, you might want to remove mushrooms in the lawn just to be on the safe side. (Truth be told, I’ve never actually done what I just said.)

Finally, unless you’re a trained mycologist or experienced amateur, you should never, ever eat wild mushrooms. Again, chances are the mushrooms in your lawn aren’t poisonous, but according to a friend who is a trained mycologist, most of them either have no taste at all or taste awful.

And that’s reason enough not to even think about eating them.

Some Like it Hot!

By Paul James

It’s safe to assume that in the weeks ahead, it’s gonna get hotter. Probably a whole lot hotter. And that can take some of the fun out of gardening, which is why I tend to get things done early in the morning. But unlike me, a considerable number of plants truly love the heat of summer, and here are some of the best to consider planting now…or at least early in the morning.

Annuals

Fact is, nearly all popular annuals used for seasonal color do well in the heat — both in the ground and in containers – but the standouts include Angelonia, Crossandra, Dichondra, Lantana, Pentas, Petunias, Portulaca, Scaevola, Sweet Potato Vine, Vinca, and Zinnia. And as luck would have it, many of them combine together beautifully and attract pollinators.

Perennials

This list is even longer, and includes Agastache (Hyssop), Alliums, Armeria, Artemesia, Asclepias (Butterfly Weed), Baptisia, Bee Balm, Coreopsis, Delosperma (Ice Plant), Dianthus, Echinacea (Coneflowers), Gaillardia, Gaura, Iris, Kniphofia (Red Hot Poker), Liriope, Nepeta (Catmint), Ornamental Grasses, Penstemon, Phlox, Rudbeckia (Black-Eyed Susan),Salvia, Sedums, Sempervivums, and Yarrow. And as luck would have it, many of them combine together beautifully, attract pollinators, and last for years.

Trees and Shrubs

In this category, darn near everything qualifies as heat tolerant, but some are exceptionally so, such as Abelia, Althea (Rose of Sharon), Barberry, Crape Myrtle, Desert Willow, Junipers, Oakleaf Hydrangea, Spirea, Viburnum, Vitex (Chaste Tree), Wax Myrtle, and Yucca. Pretty much every popular landscape tree qualifies as well. And as luck would have it, many of them combine together beautifully, attract pollinators, last for years, and are incredibly carefree.

And One More Thing

When I refer to plants as being heat-tolerant, I’m talking only about their ability to withstand the high ambient air temperatures we typically experience in July and August and much of September. I’m not necessarily talking about plants that thrive in full sun, because some of those I’ve included actually grow best with some afternoon shade or dappled light all day. Nor am I suggesting these plants are drought tolerant; in fact, many of them grow best in moist soil, and all of them require routine watering.

But you can plant with confidence anything and everything I’ve listed, knowing that when the intense heat of summer arrives and you’re chilling inside, what’s growing outside will be just fine.

Attack of the Aphids!

By Paul James

Last Sunday morning I headed out to the garden to harvest potatoes, and as I walked past my tomato plants I noticed that they were covered with aphids. Rest assured, I didn’t waste time dealing with them, because aphids can do serious damage by sucking the sap (and the life) out of plants, and they can spread nasty diseases in the process. Worse still, they reproduce at a rate – and in a fashion – that’s truly mind blowing.

Consider this: Although aphids only live a month or so, a single female can potentially produce 600 billion descendents! That’s reason enough to declare war on them at first sight, because they survive – and thrive – by the sheer force of their numbers. It’s also why it’s often said that if aphids are good at one thing, it’s reproducing.

But it’s how they reproduce that’s so fascinating, because it almost always takes place without a male mate. In biology, this reproductive method is known as parthenogenesis (meaning virgin birth), and it’s a form of asexual reproduction that’s pretty bizarre, yet very beneficial if you’re an aphid.

Here’s how it works. Female aphids produce live offspring (again, without a mate) by basically cloning themselves. That’s kind of weird, I’ll admit. But it gets weirder, because each of the female’s offspring is born pregnant! And that’s precisely how they reproduce throughout most of the spring, summer, and early fall. So by skipping the time required for an egg to hatch and develop into a sexually (or asexually) mature female, their numbers increase at an astounding rate. They also don’t waste going out on potentially awkward dinner dates.

In fact, the only time female aphids take on a male partner is in the fall. And where do the males come from? Turns out a switch turns on late in the year that enables the females to produce a few male offspring. At that point, aphids reproduce sexually (way to go, guys!) so that the females can produce eggs that are capable of surviving the winter. And guess what? The eggs that hatch the following spring are 100% female, meaning a male aphid can’t produce sons. It’s crazy, right?

So much for the sex life (or non-sex life) of aphids. The big question now is, How in the world do you control them?

And thankfully, that’s fairly simple if you get a jump on things. Releasing ladybeetles will help, but one ladybeetle can only eat about 60 aphids a day, and I’m guessing there were at least a few thousand aphids on my tomatoes. That’s why I opted to use insecticidal soap, although I might just as well have used horticultural oil or Neem oil. I sprayed the plants thoroughly, especially the undersides of the leaves where most bugs tend to hide, and later that day the aphids were dead.

But one thing’s for certain – they’ll be back. If not on my tomatoes, then on something else in my garden. After all, there are at least 250 species of aphids that prey on plants.

Here Come the Skeeters!

By Paul James

Last week I wrote about the need to fertilize plants because all the rain we’ve had lately has leached valuable nutrients out of the soil. This week I’ve got another rain-related issue to discuss, one that poses a serious risk to people, not plants. And that’s mosquitoes, the deadliest animal on the planet.

(I first posted this back in May of 2017, but the information is still solid…and timely.)

A small percentage of people on the planet don’t get mosquito bites. I’m one of them. My daughter in law and granddaughter, on the other hand, can be sitting right next to me on the patio and get two dozen bites in five minutes. So what gives? And what can they do to protect themselves?

First, the what gives. Turns out mosquitoes don’t like the way I smell, and according to microbiologists who study such things, that’s due to a particular scent emitted by the trillion or so bacteria that inhabit my skin. (And for the record, most people think I smell just fine, thank you.)

But the bacteria that live on my daughter’s and granddaughter’s skin emit an odor that’s apparently and unfortunately attractive to mosquitoes, which explains why they’re both basically mosquito magnets. And by the way, there’s nothing they can do to change that.

Now let’s talk protection. First and foremost, you have to eliminate the habitat mosquitoes love, and that’s standing water – in plant saucers, in wheelbarrows, in clogged or sagging gutters, in kiddy pools – anywhere and everywhere water remains for more than a few hours. And you’ve got to encourage your neighbors to do likewise, because mosquitoes can and most likely will travel from their yard to yours.

Bt dunks, donuts, or granules should be used in birdbaths, water features, holes in trees where water collects, and anywhere else standing water can’t be eliminated. The particular type of Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis) used to control mosquitoes is an all-natural biological control that targets only mosquito larvae. It’s extremely effective and safe to use around people and pets.

Beyond that, you need to rely on repellents, of which there are many. When trying to control mosquitoes on the patio, options include citronella candles (which may also contain rosemary, thyme, and other oils), incense sticks that also contain those and other oils, and various sprays. Deet is still the most effective spray, but a lot of folks think it’s harmful, despite considerable research to the contrary. Picaridin, an alternative to Deet that was developed in Australia, has for decades been used there and throughout Europe with no reported health risks. Plants such as citronella and lemon grass, despite what you may have heard or read, simply do not work unless you crush the leaves and rub them on your skin. However, a powerful fan will work because mosquitoes can’t fly in winds above 7mph.

For broader control, there are also repellents that contain various natural oils, are pleasantly scented, and can be applied as granules or sprays to the entire yard. Many of them last for up to three weeks depending on rainfall. And there are chemical foggers, including automated systems that spray chemicals in the air at preset intervals. I’m not too keen on having chemicals in the air while I’m hanging out in the yard, but then I’m the guy who doesn’t attract mosquitoes.

As for installing bat and purple martin houses, research makes it clear that while both critters do indeed eat mosquitoes, neither can eat enough in a day to make a noticeable dent in the population. After all, even though female mosquitoes generally don’t live longer than a week, they lay up to 300 eggs a day.

And finally, there’s one sure way to actually attract mosquitoes, and that’s to drink a beer. Mosquitoes are attracted to carbon dioxide, and there’s plenty of that in the beer and the belches that invariably follow.

It’s Time to Fertilize!

By Paul James

The relentless storms have taken their toll on area gardens, and while much of the damage is visible – flooding, downed trees, and so on – it’s what you can’t see that concerns me, and that’s the leaching of nutrients through the soil as a result of torrential and incessant rains.

Leaching occurs when water moves down through the soil and carries with it many of the nutrients that plants need to survive. And given all the rain we’ve had lately, it’s a safe bet that whatever the nutrient levels were in your soil at the beginning of May, they’re a tiny fraction of that now. That’s especially true of nitrogen and sulfur, but my guess is several micro- and secondary-nutrient levels have dropped as well, perhaps even significantly in some cases.

And that’s why you need to fertilize. I strongly recommend the use of slow-release fertilizers because they’re not particularly water soluble. As a result, they release their nutrients slowly over time. Most slow-release fertilizers are also all-natural or organic – Milorganite is a good example, as are various products made by Espoma – but there’s also Osmocote, a synthetic fertilizer that’s coated with a material that dissolves slowly and releases nutrients over a period of months. And don’t forget good old compost, whether homemade or store bought.

And just when should you fertilize? Well, now would be a good time.

Enough Already!

By Paul James

I love rain, especially when it follows a long day of planting or starts right after I’ve finished mowing the lawn. But too much of a good thing is rarely a good thing, and too much rain can wreak havoc in the garden, often in some rather unsuspected ways.

Perhaps the biggest problem is that too much rain can actually drown plants, because all that water in the soil fills spaces that would otherwise contain oxygen. When that happens, plants aren’t able to respire (or breathe, if you will) and therefore suffocate. Carbon dioxide and ethylene gases can also accumulate, both of which can be toxic to plants.

Symptoms of waterlogged soils include plant leaves turning yellow or brown or wilting suddenly. Die back of new shoots is also fairly common. And unfortunately, short of waiting for the soil to dry out, there’s not a lot you can do to reverse the situation. Pulling back the mulch from around plants (or the entire garden) will facilitate drying somewhat, as will stabbing a garden fork in the soil, which also allows oxygen to reach into the soil.

Too much rain can also leach essential nutrients out of the soil, especially nitrogen, so once the soil dries out a bit, consider applying a fertilizer such as Espoma Plant-Tone, Milorganite, or Osmocote, or simply topdress plants with compost.

Dirt and mud that splash onto leaves and stems may – and often do — harbor fungal spores, which is why it’s a good (if not counterintuitive) idea to wash the entire plant with a gentle mist. And on plants that are susceptible to fungal diseases – tomatoes in particular – you might want to apply a fungicide such as all-natural Serenade as a preventive measure.

But be careful where you walk! Your weight – regardless what it is – can cause severe compaction in wet soils, and compaction is the enemy of plants. If you have to work in the garden, place a board on the ground first and walk on it to minimize compaction. Walking in wet soil can also hasten the spread of fungal diseases, especially on beans.

Pollination can also be affected by heavy rains, in part because pollinators have a tough time flying in the rain, but also because heavy, wet pollen simply isn’t as effective at doing its thing. There’s not much you can do to remedy the problem short of waiting for the weather to change.

And finally, we’ve all been frustrated during those times when frequent rains make it impossible to get out and mow the lawn, and by the time it’s dry enough to mow the grass is overgrown. About the only way around the problem is to double cut: raise the deck to its highest notch, mow, then drop the deck height to your preferred level and mow again.

So there you have what you need to know about dealing with too much rain in the garden. Now I’m going to write a piece for the coming months on how to deal with drought.

Here Come the Hummers!

By Paul James

I saw my first hummingbird of the season last Monday, and it prompted me to think not only about cleaning and setting out my feeders, but also adding a few more Hummer-friendly plants in my landscape. And for those of you who are considering doing the same thing, here’s a list of plants preferred by 10 out of 10 hummingbirds.

One of the great things about this list is that not every plant blooms at the same time, which means Hummers will be hanging out in your yard for several months to come. And that’s important, because to sustain their supercharged metabolisms, they must eat once every 10 to 15 minutes and visit between 1,000 and 2,000 flowers a day!

And I thought I was a glutton.

What’s up with pH?

By Paul James

At some point, all gardeners hear the term pH, perhaps most frequently when they’re trying to change the color of their hydrangeas from pink to blue or vice versa, because the only way to do that is by changing the pH of the soil. But what the heck is pH, anyway?

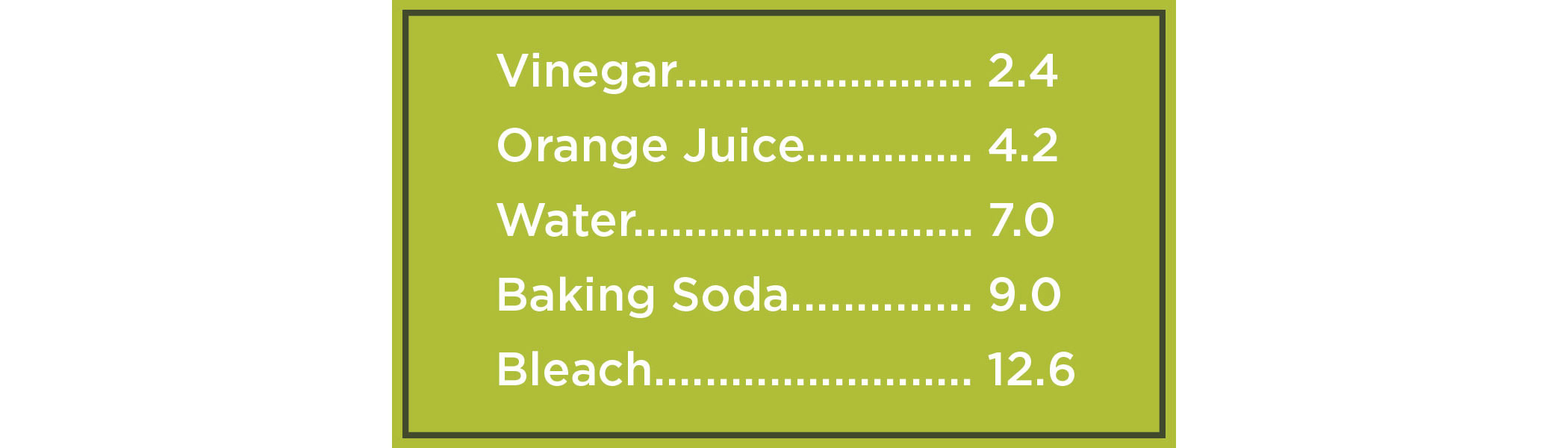

Without getting too technical, pH refers to the relative acidity or alkalinity of a substance and is measured on a scale of 0 to 14. Anything with a pH less than 7.0 is considered acidic, whereas anything with a pH above 7.0 is considered alkaline, and a substance with a pH of 7.0 is considered neutral. To understand the scale in more familiar terms, here are the pH values of some common household items.

The ideal soil pH for the vast majority of plants is close to or just below neutral, with 6.5 to 6.8 being the sweet spot. Exceptions include so-called acid-loving plants such as pin oaks, azaleas, blueberries, and gardenias, all of which prefer a pH of slightly above or below 5.0. There are also plants that do well in alkaline soils, including burr oak, barberry, Spirea, junipers, Viburnums, yews, geraniums, yarrow, daylilies, and honeysuckle, just to name a few.

If a plant isn’t growing in a soil with the ideal pH, its roots may not be able to take up important nutrients, even if the soil is loaded with nutrients, and that can lead to everything from a lack of vigor to discoloring of leaves to the outright death of the plant. A pH that is either too low or too high can also cause a toxic buildup of certain elements, including manganese in low pH soils and aluminum in high pH soils.

Thankfully, raising or lowering pH is pretty simple. To make soils more acidic (to lower the pH) you add sulfur, and to make soils more alkaline (to raise the pH) you add limestone, preferably in the form of dolomitic limestone. Neither is soluble in water, so it’ll take at least a couple of weeks for them to have an effect on your soil’s pH.

And just how do you determine the pH of your soil? The most accurate test is one done by a lab, which technicians at OSU will perform for $10. You’ll also get measurements of the amount of nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium in your soil. Just take a soil sample to a county extension office and they’ll mail it to the lab. (Click here to learn how to properly prepare a sample.) You can also buy inexpensive kits, which are nowhere near as accurate, but will at least let you know if you soil is within an acceptable range.

I suppose I could have started this blog by explaining that pH is the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the hydrogen ion activity at 25-degrees Celsius and measured in moles per liter. But then, I actually wanted you to read beyond the first paragraph.

And by the way, to change the color of your hydrangea flowers from pink to blue, you need to acidify the soil. To change them from blue to pink, you need to make the soil more alkaline. If you prefer a mix of pink and blue, shoot for a neutral pH.

Caring for Azaleas

By Paul James

The azalea show this spring has been nothing short of spectacular, thanks to near-perfect weather conditions. But as the flowers begin to fade, it’s time to take care of the plants’ nutrient needs, as well as things such as pruning, watering, and monitoring the plants for signs of insect invasion.

And by the way, the following suggestions apply both to traditional and to repeat-blooming azaleas. In other words, treat the latter as if they were the former.

Fertilizing and Pruning

Blooming zaps a lot of energy out of a plant, and azaleas are no exception. That’s why it’s best to fertilize them after they bloom. Products that combine essential nutrients with soil acidifiers to lower the pH are ideal, and one of the best is Espoma Holly-Tone. A dose of iron is a good idea too, especially if you notice the leaves turning yellow.

You should also prune right after flowering in spring, although the fact is azaleas rarely need pruning beyond removing deadwood and crossing branches.

Pest Problems

Shortly after the bloom period, be on the lookout for lace bugs, little critters that hide under the leaves. They can be a major pest, but thankfully they’re also fairly easy to control.

Lace bugs overwinter as eggs. Adult females insert their eggs into the leaf tissue and then cover them a dark splotch of a varnish-like material that seals the egg into the leaf. This, along with their shiny black droppings gives the underside of the leaves a “fly-specked” appearance. There can be more than one generation a year in Oklahoma.

To control lace bugs, thoroughly spray leaf surfaces (upper and especially lower) with insecticidal soap, horticultural oil, Neem, or a product that contains Spinosad, such as Captain Jack’s Dead Bug Brew. All are all-natural products, but they should be sprayed after sunset to avoid harming honeybees and other beneficial insects.

Mites

Spider mites are not insects, but are more closely related to spiders. They’re typically found on the underside of leaves as well. The most common type in this area is the red spider mite, and like the lace bugs, spider mites suck plant sap and cause the leaves to change color from bright to dull green, and with a heavy infestation, leaves may turn gray-green or bronze-green. Leaves may also be covered with webbing. Control them using the same products recommended for lace bugs.

Mulch

Because they are shallow rooted, azaleas benefit greatly from a thick layer of mulch, whether chipped or shredded wood products, or pine straw. Maintain a two- to four-inch layer. Replenish each spring and fall.

Water

One inch of water per week should be enough to keep azaleas healthy. Watch for signs of dryness with newly planted azaleas, especially if they were planted high or located in a windy area. Drooping leaves indicate the need for supplemental watering well before the plant dries out completely. Water slowly and deeply to ensure the rootball gets plenty of moisture and the plant should rebound quickly.

In Praise of Japanese Maples

By Paul James

For years, I’ve been asked repeatedly, “What’s your favorite plant”? It’s a difficult question to answer, because there are so many incredible candidates. But the other day, while pruning my Acer palmatum ‘Shishigashira’ bonsai, I came to the realization that my favorite plant – or more specifically plant group – would have to be Japanese maples.

I’ve always been captivated by their amazing diversity in terms of leaf color and shape, range of sizes, and by their many and varied forms, whether upright or weeping. And I’ve always been impressed by how incredibly tough they are, despite their seemingly delicate appearance.

Best of all, perhaps, is the fact that they’re easy to grow, provided you plant them in the right spot to begin with. That means an area where the soil contains a decent amount of organic matter and drains well, and ideally gets just a few hours of morning sun followed by shade the rest of the day, or dappled light throughout the day.

Beyond that, Japanese maples don’t require that much attention. The weeping varieties do need light pruning to remove deadwood in their interior, and the upright forms may need a touch up every other year or so, but it’s best to keep pruning to a minimum. The same is true of fertilizer: Japanese maples simply don’t need much of a nutrient boost beyond a topdressing of compost twice a year, or a light application of a slow-release, low-nitrogen organic fertilizer in spring and fall.

However, because they have shallow root systems, plan on applying a thick – as in 3-inch – layer of bark mulch around the base of each tree to maintain fairly even moisture, something all Japanese maples require.

I could provide you with a long list of species and varieties of Japanese maples I adore, but I won’t. Instead, I would encourage you to discover for yourself the ones you like best, knowing that at the end of the day, you really can’t go wrong with whatever you choose.

Mulch – Like Icing on the Cake

By Paul James

If you consider the money you spend on plants as an investment of sorts (and you really should), then you should also know that the smartest way to protect and insure a return on your investment is to apply mulch to your garden beds. Here’s why.

By using mulch in the garden, you’re mimicking what nature has been doing for eons – covering, and thereby protecting and enriching the soil with organic matter. Deciduous trees and shrubs blanket the forest floor with leaves that prevent erosion, maintain soil moisture, and prevent noxious weeds from germinating. As those leaves decompose, they provide nutrients to plants and food for soil-dwelling critters, especially earthworms, and they improve the soil’s structure and tilth. When you mulch at home, you’re doing essentially the same thing. And you get an aesthetic bonus too, because mulch is beautiful. To me, it’s like icing on the cake.

There are lots of different organic mulches on the market, and you really can’t go wrong with any of them. Chipped or shredded wood mulches are by far the most common. Pine needles are big in the south, and are gaining in popularity here as well. But mulch can also be nothing more than a layer of shredded leaves, compost, or any number of bagged products sold as soil conditioners.

Whatever you choose to use, a two- to four-inch layer is ideal, and ideally applied in spring and again in late fall. Spread the mulch evenly, tucking it up to the base of plants without covering their crowns to discourage rot. Don’t create pyramids of mulch at the base of trees – not only can that cause serious pest and disease problems, it also looks weird. (I sure hope my neighbor is reading this!)

And speaking of weird, don’t freak out if you see white strands of fungus growing in your wood-based mulch. That’s actually a beneficial fungi that’s helping break down the wood and converting it into plant nutrients.

The only possible downside to mulching heavily and regularly is that you may have to water a little more each time you water, because the water has to percolate through the mulch to get to the roots of plants. But you can also water less frequently. Which means it all comes out in the wash, so to speak.

Soil is Alive!

By Paul James

That’s right. Soil is alive. It’s a living organism. And until you get your head around that concept, you’ll never really get gardening. Sorry, but it’s true. So make those three words your gardening mantra. Carve them into the handle of your favorite shovel. Paint them graffiti-style on your fence. Shout them out at the top of your lungs for all your neighbors to hear!

But just what do I mean when I say soil is alive? Well, consider the following.

More organisms occur in soil than in all other ecosystems combined. In fact, in just one tablespoon of soil there are more living things than there are people on the planet. (You might want to read that sentence again. It’s pretty mind blowing.) And in that one tablespoon lives a diverse and dynamic community composed of all sorts of critters, some of which you can see, most of which you can’t. But all play a vital role in keeping the soil healthy…and alive.

Soil Mates

I want you to meet these critters, and learn to appreciate all they do for us, which is a lot. After all, without them, life as we know it would cease to exist. Seriously. They’re that important.

Bacteria

In one teaspoon of soil, there are as many as 100 million bacteria, most of which reside in the top six inches. These single-celled microorganisms reproduce by cellular division at an astounding rate. In fact, a single bacterium can produce 47 million descendants in 12 hours! Their population tends to remain fairly stable simply because they die at a rapid rate as well, and because many of the other critters you’re about to meet like to eat them.

Bacteria are responsible for such things as nitrogen fixation and sulfur oxidation, processes that make essential nutrients available to plant roots. They also aid in the decomposition of organic matter. Without them, plants simply cannot grow.

However, there are harmful bacteria as well, namely those that cause annoying and difficult to control plant diseases such as blight, leaf spot, and certain cankers. But hey, you’ve got to take the good with the bad.

Fungi

Fungi are multicellular organisms that account for the greatest amount of living mass in soil. And within the world of fungi, there are the good, the bad, and the downright ugly.

Most gardeners, when they hear the term fungi, think of those that are harmful to plants, from powdery mildew on cucumbers to rust on roses to fusarium wilt on tomatoes. But there are all kinds of beneficial fungi as well. Many of them are saprophytic scavengers (they feed on all those dead bacteria), but their varied diet also includes leaf litter and other organic matter. There are also fungi such as mycorrhizae that enter into a symbiotic (mutually beneficial) relationship with the roots of plants to facilitate nutrient uptake.

So not all fungi are bad. In fact, some are quite good, especially mushrooms, morels, and truffles. Yummy!

Actinomycetes

Ever wonder what makes soil smell sweet? Or why the air smells so good after a spring rain? Well, it’s all due to Actinomycetes, a sort of cross between bacteria and fungi. These single-celled organisms devour the tough, woody stuff in the soil – chitin, lignin, and cellulose – as well as phospholipids (a fancy word for fats). In the process, they produce geosmin, the compound that gives the soil its distinctive, earthy smell. That smell is so enticing that geosmin is sometimes added to perfumes to give them an alluring earthiness. Eau de Compost, anyone?

Chances are you’ve seen Actinomycetes colonies in your own soil or mulch or compost pile. They look like grayish-white spider webs, and they’re a sign that your soil is healthy. So don’t freak out.

Actinomycetes also have antibacterial properties, which explains why Streptomycin and related antibiotics come directly from Actinomycetes.

Algae

Algae are bit players, really. They primarily live on rather than in the soil, because they contain chlorophyll and therefore need light to grow. Other critters dine on them.

Protozoa

These “animals” include amoeba and paramecium, both of which you probably observed under a microscope in science class. They reside in the top six inches of soil, where they graze on bacteria while other critters graze on them.

Nematodes

Again, most gardeners think of nematodes as bad guys, and some are. But soil is full of beneficial nematodes, and they comprise as much as 90 percent of the multicellular invertebrates in the soil. Millions can be found in a single shovel-full of good garden soil. Think of them as microscopic roundworms, chomping on fungi and recycling nutrients into the soil.

Bigger Critters

This group includes the more familiar forms of life – ants, beetles, crickets, earthworms, grubs, millipedes, mites, slugs, and so on. Collectively, you can think of these guys and gals (or in some cases, both) as nature’s rototillers, because as they move through the soil in search of food, they aerate it. They also leave behind their nutrient-rich poop.

But just what do they – and all their fellow soil mates – actually eat, besides each other? Organic matter in its myriad forms, that’s what. And that’s why the only way to keep soil alive is by adding lots of organic matter – shredded leaves, grass clippings, homemade compost, barnyard manures, or bagged products from Fox Farm, Back to Nature, and other companies committed to keeping soil healthy…and alive.

Damage Assessment

By Paul James

Morning lows earlier this week were colder than a polar bear’s paws. As a result I had at least a dozen friends ask me what effect, if any, the way-below-freezing temperatures might have had on landscape plants. My responses ranged from “We’ll have to wait and see” to “It’s a goner” depending on the plant in question. Here’s why.

Sometimes freeze damage on a plant is obvious – the plant wilts, and its leaf tissue turns from green to black to mushy. It’s not a pretty sight. That’s precisely what happened to tender vegetation, especially vegetables and herbs that were just emerging or recently transplanted. Those plants are goners, but there’s still plenty of time to replant. What’s growing below ground, such as potatoes or asparagus, will be just fine.

Sometimes a plant will wilt but show no obvious signs of tissue damage. For example, I saw wilt on the terminal growth of Photinias all over town. If it doesn’t bounce back by the weekend, you should consider pruning the tips back several inches. Aucubas look as though they’re dead already, but they’ll recover nicely.

In many cases the effects of freeze damage can be delayed for several weeks, and that’s definitely going to be the case with many early-spring bloomers, including forsythia, saucer magnolia, quince, fruit trees, and maybe even redbud and dogwood. Their flower buds may well have been zapped, but the plants themselves will recover. And by the way, azaleas and hydrangeas should be fine, both foliage and flowers.

I actually expected to see a fair amount of damage on daffodils, but mine – and those throughout my neighborhood – look great. The foliage shows no signs of tissue damage, and even the flowers appear to be just fine.

The bottom line is that 99.9% of all landscape plants were unscathed by the weather, largely because they’re plenty hardy but also because they’re still dormant. Let’s just hope we don’t see any hard freezes this spring.

Moles on the Move!

By Paul James

A post about moles may seem decidedly unromantic on Valentine’s Day, but bear with me. You see moles are making their moves, so to speak, evidenced by their extensive tunneling. And while they’re certainly on the hunt for food, they’re also hunting for a mate. Yes, my friends, it’s mole mating season, the most romantic time of the year for moles.

The tunnels you see aboveground are known as runways, in which moles feed and also use as pathways to deeper tunnels and their lairs. They may use the runways for several days so long as food is present, or they might abandon them after only one day of digging if food isn’t present, only to immediately create another.

Fortunately, moles don’t eat plants (voles and gophers do, but that’s another story). Instead, they prefer a steady diet of primarily white grubs and earthworms, which they consume in huge quantities as they tunnel through lawns and gardens.

A vast array of runways may cause you to think that there are dozens of moles in your yard, but in fact moles are very territorial, and rarely are there more than three in an entire acre (except perhaps this time of year) so typically the average-size yard is harboring only one. Of course, even one can be a nuisance.

So just how do you go about controlling moles? Well you could do nothing, and embrace the mole’s presence, knowing that he or she is gobbling up the grubs that might ultimately become Japanese beetles and attack your roses, and aerating the soil in the process.

You could try repellents, nearly all of which contain castor oil and do a pretty good job of moving moles elsewhere assuming you follow the label instructions to the letter and reapply after heavy rains. I’ve actually had excellent results with repellents.

You could use harpoon-style traps, which if placed properly can be highly effective, if not a tad gruesome.

You could hire an exterminator. They don’t come cheap, and some don’t even guarantee that they’ll be successful, but folks in my neighborhood who’ve relied on their services have been pleased with the results.

You could try poisons, but realize that moles aren’t likely to eat anything that doesn’t resemble a grub or earthworm, so poisons that control mice and other critters won’t work. Even the poison “worms” are only marginally effective at best, because moles can tell the difference between real and fake worms.

And finally, you could consider any number of different home remedies, from stuffing tunnels with dog or cat hair to flooding the tunnels to using Juicy Fruit gum (which the moles are said to eat, but are unable to digest). Just keep in mind that the effectiveness of these approaches is purely anecdotal, with no basis whatsoever in science.

Regardless of the method you try, you don’t want to wait much longer. That’s because the gestation period for a female mole is about 45 days, which means a new generation of moles will be here around April 1. No fooling.

Beyond the Bouquet

By Paul James

I’ve never swooned my sweetie with cut flowers on Valentine’s Day, because I don’t want to express my love with something that’s here today, gone tomorrow. And a dozen, grossly overpriced (and often fragrance-free) roses always struck me as a predictable, last-minute decision. That’s why I prefer to go beyond the bouquet and give live plants instead.

And thankfully, there are dozens of great choices, especially among flowering houseplants. Here are a few of my favorites.

There are also dozens of great choices among foliage plants, including the oh-so-very-easy-to-grow ZZ plant, Chinese evergreen, Snake plant (Sansevieria), Spider plant, Aloe Vera, Pothos ivy, Dumbcane (Dieffenbachia), and Pony-Tail palm.

I haven’t decided which plant to get my wife, Carrie, this year. But one thing’s for sure – I won’t be giving her a bouquet.

A Perfect Weekend for Gardening!

By Paul James

The forecast for this weekend looks absolutely fantastic for getting things done in the yard. And you can bet your begonias I’ll be taking advantage of the warmer-than-average temperatures by tackling more than a few tasks. In case you plan on doing likewise, here’s a list of things to consider.

Plant Trees, Shrubs, and Roses

It’s the perfect time to get deciduous trees and shrubs, including roses, in the ground. And now is also the best time to see their “bones” or bare branches. I actually prefer to select these plants on the basis of their branching alone, because it gives me a better idea of what they’re going to look like once they’re loaded with leaves.

Prune

I plan on pruning several small trees and shrubs with an eye toward removing dead or crossing branches, and opening up the interior of the plants. I’ll also be trimming ornamental grasses and cutting back a few perennials. I’ll wait until we get closer to spring to prune evergreens and conifers.

Plant from Seed

Sowing from seed indoors, whether flowers or vegetables or both, is a lot of fun, and you typically have more choices available. What’s more, it’s extremely economical. We’ve got pretty much everything you need to get started, including biodegradable and plastic pots, trays (even self-watering versions), heating mats to boost germination and seedling growth, lights, potting mixes…and seeds, of course!

Water!

I’m going to deep soak everything in my landscape on Sunday afternoon, including the lawn, and especially evergreens. It hasn’t been all that dry this winter, but I plan on seizing the opportunity to water anyway.

Weed Control

Want to control pesky weeds in the lawn? Now is the time to do just that by applying a non-selective herbicide (on dormant Bermuda grass only) or a pre-emergent herbicide. We’ve got several products to choose from, but keep in mind that different products control different weeds, and timing their application is fairly critical, so visit our Solution Center to find out which one is right for you.

Make the Most of Leaves

If you’ve still got leaves lying around, do a final cleanup. Use a mulching mower to shred leaves into fine particles, which will add organic matter and nutrients to your lawn. Rake leaves in your flower beds and toss them into your existing compost pile, or use them to start a new one. Composted leaves are the greatest soil amendment money can’t buy, and ultimately they can transform any soil type – from heavy clay to pure sand – into something plants will love to call home.

Get Equipment Repaired

Beat the spring rush by having your power equipment serviced now. If you wait another month, you’ll wind up waiting weeks rather than a few days to get your mower or blower back, and by then it’ll be time to mow and blow.

Clean Garden Tools

Use a steel brush to knock dirt and rust off metal surfaces, then apply a thin layer of oil (Canola works great) and rub it in with a cloth. Rub wooden handles of tools with boiled linseed oil and they’ll last for years to come. And finally, sharpen shovels, hoes, pruners and other cutting tools with a file, or check out the sharpening gizmos we carry.

Plant Veggies?

I’m tempted to plant potatoes and onions this weekend, but I can’t in good faith suggest you do the same. I might even stick a few cole crops –broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower – in the ground, knowing that there’s a good chance I’ll have to cover them once or twice in the weeks ahead. But because the long-range weather forecast looks pretty mild, and because my raised beds warm up quickly on sunny days, I’m probably going to take a chance on getting a few things in earlier than usual.

And if all goes well, I’ll be harvesting earlier than usual too. Yippee!

Soil Test, Anyone?

By Paul James

When is the last time you had your soil tested? Or perhaps more to the point, have you ever had your soil tested? Chances are the answer to the first question is “Can’t remember,” and the answer to the second is “No.” And that’s too bad, because a soil test can reveal problems you never knew you had and make a huge difference in how well your plants grow.

Thankfully, getting a soil test is a pretty simple and inexpensive procedure, and you don’t have to study for it. What’s more, it’s not something you need to do every year. Actually, I’d suggest you consider testing only every three to five years or so, because changes in soil chemistry generally don’t occur very rapidly.

A basic soil test performed by folks at OSU’s Soil Science Lab will reveal four things about your soil: its nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium (or NPK) levels, and its pH. That’ll cost you $10. You can pay more to get more, including such things as secondary and micronutrient levels, and well as organic matter content, but those tests aren’t all that necessary for homeowners.

To prepare a soil sample, you’ll need a clean trowel, a bucket, and a one-quart zip-lock plastic bag. Use the trowel to dig up the soil to a depth of roughly six inches, and collect at least a dozen or so two- or three-tablespoon samples from several locations in your lawn, flower bed, or veggie garden. (Consider each location as a separate test.) Drop the samples in the bucket as you go, then mix the soil well and remove any sticks or other debris.

Fill the plastic bag with the mixed soil, and take the sample to the OSU Extension office at 4116 East 15th Street. Within two or three weeks, you’ll receive the test results along with recommendations on the nutrients you need to add and how much. You might even learn that you should stop adding certain nutrients.

Fair warning: Interpreting the test results can be a bit confusing, but don’t let that discourage you. Just bring the information to our Solution Center, and let Jennifer or Taylor give you step by step instructions on how to make the necessary adjustments to your soil’s NPK and pH levels so that your plants will be healthy and happy all season long.

Do Bugs Survive Winter?

By Paul James

A lot of folks claim that freezing temperatures reduce insect populations. But does that claim have any basis in fact? Not really. Yes, a few bugs will bite the dust, but most have developed truly remarkable (and downright cool) ways of protecting themselves and furthering their progeny.

The simplest way insects beat the cold is by migrating to a warmer spot, just as Monarch butterflies do. Moving into your house is another common means of survival for numerous insects including crickets, ants, ladybugs, stink bugs, moths, and even wasps.

Insects that can’t survive cold temperatures – both those that prey on plants as well as their beneficial counterparts — at least know how to sustain their populations by laying eggs underground, in leaf litter or garden refuse, and in buildings.

And what about fleas and ticks and mosquitoes? Sorry. More not-so-great news.

Fleas are clever enough to find ways to stay warm, whether on wild or domesticated animals or in garages, under decks, and around foundations.

Ticks begin a process of acclimation long before winter arrives by moving water out of their cells before it freezes and crystallizes, thereby allowing them to survive freezing temperatures. They also escape the cold beneath leaf litter and other warm spots.

Mosquitoes actually hibernate both inside and out. They also lay eggs in the fall that can survive the cold – even in frozen water — and remain dormant until spring.

And there are some insects – the Emerald Ash Borer for example, as well as some mosquitoes – that produce a sort of antifreeze in their blood called glycerol, which enables them to survive freezing temperatures in a state of suspended animation. It’s insect cryogenics, basically.

Let’s face it. Insects have been around for millions of years, and rarely do we hear of them becoming extinct. They’ve survived predators, pesticides, an asteroid that killed off the dinosaurs, and yes, even nuclear explosions. Among living things, they are the ultimate survivors.

And you think something like a little cold weather is going to affect them?

Winter Houseplant Care

By Paul James

Winter can be a tough time for tropical houseplants. Light levels indoors are less intense. Humidity levels typically drop way below the comfort level of most plants. But perhaps most critically, folks tend to water and fertilize their houseplants in winter the same way they do throughout the rest of the year. And that’s a big boo-boo.

Light

Because of the sun’s lower angle in winter, light levels indoors can drop a whopping 50%, so plan on moving plants closer to windows or to an area that gets more light (such as a southern or western exposure). Just make sure plant leaves don’t touch the glass. Also, consider cleaning you windows to maximize light transmission, dusting plant leaves so they can absorb all the light available, and rotating plants a quarter turn each week for even light distribution.

If your plants need more light than is naturally available, add artificial light in the form of standard fluorescent tubes or lights made specifically for growing plants, such as high output LEDs.

Humidity

The majority of houseplants prefer humidity levels of around 50%, yet in most homes in winter humidity typically hovers around 10%. The most common sign of plant stress resulting from low humidity is browning on leaf margins. Spider mites might also rear their ugly heads.

The surest way to increase humidity is to mist plants often – at least once, maybe even twice a day. Placing plants on a tray filled with moist pebbles also works well. But the simplest and most effective solution is a small humidifier – Duh! Just run it once or twice a day for half an hour or so and your plants will love it. As a bonus, the higher the humidity, the less you’ll have to water.

Water

Without a doubt, the most common cause of houseplant failure is overwatering, and the most common season for failure is winter. Here’s why.

During most of the year, houseplants are actively growing and therefore need regular watering. But growth slows down considerably in winter, so you need to adjust your watering schedule. In the case of most houseplants, it’s best to let the soil dry out almost completely before watering (exceptions would be ferns and citrus, which need steady moisture).

But exactly how do you know when to water? Just poke your finger two inches into the soil. If it’s dry, go ahead and water.

Fertilizer

Again, because plants grow very slowly in winter, they don’t need much if any fertilizer. And applying fertilizer at a time when plants don’t need it is more than just a waste of money – it can also lead to burning of the roots and a buildup of salts in the soil.

Repotting

Finally, and again because houseplants go partially dormant in winter, it’s best to hold off on repotting until spring, when active growth begins. That’s also when you should begin fertilizing again and watering more frequently.

Let it Snow?

By Paul James

It looks as though we could be in for a doozey of a winter storm this weekend that may include ice and snow. So what effect, if any, could freezing precipitation have on landscape plants, and is there anything you need to do in preparation for the storm? Glad you asked.

For the most part, snow is a good thing. Snow is mostly air trapped in ice crystals, and that trapped air acts as an insulator, preventing plant tissues from dropping below freezing. It insulates the soil in the same way, keeping it at or above freezing even when air temperatures plunge.

Wet, heavy snow may bend the branches of evergreens, but as bad as it looks, most of the time the branches will spring back once the snow melts.

Snow has even been called “Poor Man’s Fertilizer,” because as it falls through the atmosphere, nitrogen and sulfur attach to the flakes. That’s actually true, but rain and lightning contain even more nitrogen. And come spring you’ll still need to fertilize.

And yes, snow provides moisture, but not as much as you might think: ten inches of snow equals about an inch of water.

Ice is another story. It sucks. And it can do serious damage. It does insulate plant tissues in a manner similar to snow, but the weight of even a quarter inch of ice can be devastating, as anyone who was around here in 2007 can attest. Whatever you do, don’t try to knock ice off of branches with a stick because you may (and probably will) do far more harm than good.

In terms of preparing for the storm, I’d suggest a trip to your favorite grocer. The weekend looks ideal for cooking beef bourguignon, ragu Bolognese, or maybe a big old pot of chili, all of which freeze well. And don’t forget the vino.